IT'S IN THE CARDS

Creating this page was not the pedestrian endeavor first envisioned. In addition to being dealt off the bottom, whoever decided to create the following timeline had to be a real card. And please acknowledge the restraint just exhibited by using "a real card" instead of "a real joker". Another example of Brianetics' devotion to stylistic integrity.

868: Chinese writer Su E describes Princess Tong Cheng playing the “leaf game” with her husband’s family, the Wei Clan. This makes the Tang Dynasty the earliest official mention of playing cards in world history.

1005: Ouyang Xiu, another Chinese writer, associates the rising popularity of playing cards with the production of sheets of paper instead of the traditional scrolls.

1300s: Playing cards come to Europe—which we know because in 1367, an official ordinance mentions them being banned in Bern, Switzerland.

1377: A Paris ordinance on gaming mentions playing cards, meaning they were so widespread that the city had to make rules to keep players in check.

1400s: Familiar suits start appearing on playing cards across the world—hearts, bells, leaves, acorns, swords, batons, cups, coins.

1418: Professional cardmakers in Ulm, Nuremberg, and Augsburg start using woodcuts to mass-produce decks.

1430-50: The Master of Playing Cards arrives in Germany. Nobody knows who this guy actually is, but it seems that, unlike other card producers of the day, he trained as an artist as opposed to an engraver, making him unique in the business. His playing cards were far more artistically sound than his predecessors.

1480: France begins producing decks with suits of spades, hearts, diamonds, and clubs. The clubs are probably a modified acorn design, while the spade is a stylized leaf.

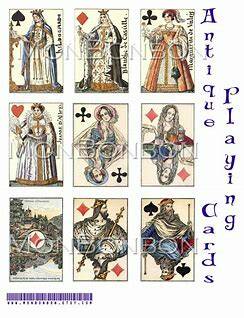

Late 1400s: By the end of the century, European court cards switch from current royalty to historical or classic figures.

1500s: Rouen, France, becomes England’s primary provider of playing cards, while a Parisian design swept France. It’s the Parisian design we’re most familiar with today.

1790s: Before the French revolution, the king was always the highest card in a suit; the Ace begins its journey to the top.

1867: Russell, Morgan, & Co is founded in Cincinnati, Ohio as a company that prints theatrical and circus posters, labels, and playing cards.

1870s: The Joker makes its first appearance as the third and highest trump (the best bower) in the game of Euchre. Some believe the name “joker” is actually derived from the word “juker,” another name for Euchre.

1885: The first Bicycle® Brand cards are produced by Russell, Morgan, & Co.

1894: Russell, Morgan, & Co. becomes The United States Playing Card Company, acquiring the Standard Playing Card Company (Chicago), Perfection Card Company (New York), and New York Consolidated Card Company (also New York).

1939: Leo Mayer discovers a Mameluke deck (cards made in Mamluk Egypt) in Istanbul dating from the 12th or 13th century.

1942: The United States Playing Card Company begins producing Bicycle® Spotter Decks to help soldiers identify tanks, ships, and aircraft from other countries. They also produced decks for POWs that pulled apart to reveal maps when moistened.

1966: During the Vietnam war, two lieutenants write The United States Playing Card Company to request decks containing nothing but Ace of Spades cards. The cards frightened the highly superstitious Viet Cong, who believed Spades predicted death.

2013: The United States Playing Card Company founds Club 808, prompting the biggest Bicycle® playing card fans from all over the world to join together to read great articles, hear from celebrity card players, and get cool stuff. Welcome to the club.

Sources:

Caldwell, Ross Gregory. “Early Card Painters and Printers in Germany, Austria, and Flandern (14th and 15th Century).” Playing Cards. 2003. http://trionfi.com/0/p/20/. 14 April 2013.

MacPherson, Hugh. “The History of Playing Cards.” Textualities. 2009. http://textualities.net/hugh-macpherson/the-history-of-playing-cards/ 15 April 2013.

Parlett, David (1990), The Oxford Guide to Card Games, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-214165-1

Wilkinson, W.H. (1895). “Chinese Origin of Playing Cards.” American Anthropologist VIII (1): 61–7

Playing cards are known and used the world over—and almost every corner of the globe has laid claim to their invention. The Chinese assert the longest pedigree for card playing (the “game of leaves” was played as early as the 9th century). The French avow their standardization of the carte à jouer and its ancestor, the tarot. And the British allege the earliest mention of a card game in any authenticated register.

Cards have been used for gambling, divination, and even commerce. But where did their “pips” come from?

The birthplace of ordinary playing cards is shrouded in obscurity and conjecture, but—like gunpowder or tea or porcelain—they almost certainly have Eastern origins. “Scholars and historians are divided on the exact origins of playing cards,” explains Gejus Van Diggele, the chairman of the International Playing-Card Society, or IPCS, in London. “But they generally agree that cards spread from East to West.”

Scrolls from China’s Tang Dynasty mention a game of paper tiles (though these more closely resembled modern dominoes than cards), and experts consider this the first written documentation of card playing. A handful of European literary references in the late 14th century point to the sudden arrival of a “Saracen’s game,” suggesting that cards came not from China but from Arabia. Yet another hypothesis argues that nomads brought fortune-telling cards with them from India, assigning an even longer antiquity to card playing. Either way, commercial opportunities likely enabled card playing’s transmission between the Far East and Europe, as printing technology sped their production across borders.

In medieval Europe, card games occasioned drinking, gambling, and a host of other vices that drew cheats and charlatans to the table. Card playing became so widespread and disruptive that authorities banned it. In his bookThe Game of Tarot, the historian Michael Dummett explains that a 1377 ordinance forbade card games on workdays in Paris. Similar bans were enacted throughout Europe as preachers sought to regulate card playing, convinced that “the Devil’s picture book” led only to a life of depravity.

Everybody played cards: kings and dukes, clerics, friars and noblewomen, prostitutes, sailors, prisoners. But the gamblers were responsible for some of the most notable features of modern decks.

Today’s 52-card deck preserves the four original French suits of centuries ago: clubs (♣), diamonds (♦), hearts (♥), and spades (♠). These graphic symbols, or “pips,” bear little resemblance to the items they represent, but they were much easier to copy than more lavish motifs. Historically, pips were highly variable, giving way to different sets of symbols rooted in geography and culture. From stars and birds to goblets and sorcerers, pips bore symbolic meaning, much like the trump cards of older tarot decks. Unlike tarot, however, pips were surely meant as diversion instead of divination. Even so, these cards preserved much of the iconography that had fascinated 16th-century Europe: astronomy, alchemy, mysticism, and history.

Some historians have suggested that suits in a deck were meant to represent the four classes of Medieval society. Cups and chalices (modern hearts) might have stood for the clergy; swords (spades) for the nobility or the military; coins (diamonds) for the merchants; and batons (clubs) for peasants. But the disparity in pips from one deck to the next resists such pat categorization. Bells, for example, were found in early German “hunting cards.” These pips would have been a more fitting symbol of German nobility than spades, because bells were often attached to the jesses of a hawk in falconry, a sport reserved for the Rhineland’s wealthiest. Diamonds, by contrast, could have represented the upper class in French decks, as paving stones used in the chancels of churches were diamond shaped, and such stones marked the graves of the aristocratic dead.